About the Project

Field Guide to a Crisis (FGC) is a socially engaged art project that began in 2020, created by Justin Maxon and co-conceptualized with Marina Lopez. FGC was launched in response to the challenges the substance abuse recovery community faced during the COVID-19 pandemic. The project serves as a training tool, mentoring residents of sober living homes to become “educators in resiliency.”

FGC recognizes the resilience and adaptability of individuals who have navigated crises and isolation, emphasizing the practical skills they have developed through these experiences. Participants showcase their crisis resilience skills through lesson plans, instructional videos, public presentations, and performances. By elevating lived experiences to expert knowledge, FGC challenges societal norms regarding the value of individuals, thereby fostering new forms of expertise. As a result, those once marginalized become educators and leaders, reshaping our community’s response to the crisis.

FGC has been generously funded by the California Arts Council, the National Geographic Society, the Center for Photographic Arts, the Humboldt Area Foundation, and the Wave Pool Gallery.

Justin Maxon is an award-winning photographer and social practice artist committed to engaging with communities and creating work that challenges systemic power structures, often addressing issues such as race, class, addiction, and representation. His practice is interdisciplinary and collaborative, utilizing photography alongside video, performance, narrative, and sculptural forms to create dialogical spaces that build inclusivity, community participation, and the value of person and place. He uses his experience in recovery to deconstruct the societal stigma surrounding substance abuse.

Creator:

Justin Maxon

Project conceptualizer:

Marina Lopez

In collaboration with:

Allonte Hart

Loretta Davis

Olivia Nava

Sarah Northrop

Drawings:

Monté Jones

Juliana Artemov

Essay:

Cal Cullen

Designer:

Eric Blyth and Cereal Box Studio

Editing:

Kye Grant

Mentorship:

Maria Seda-Reeder

Harrell Fletcher

Marina Lopez

This project could not have happened without the many participants who contributed their stories and words of wisdom: Nakeisha Alcorn, Qiana Baggett, Jatana Bowling, Ryan Brilmagen, Randall Burger, Jessica Burson, Ashley Call, Robert Crawford, Jaleesa Dillingham, Chelsea Evan, David Gadson, Ashley Hackworth, Allonte Hart, Vicent Hillman, Anita Jelks, Brenda Johnson, Gene Moses, Sarah Northrop, Javonya Ogle, Angela Price, Bethany Ragland, Mike Speckter, Mike Stallworth, Jessica Taylor, John Edward Thurman, Kiara Ward, Amanda Stacie Ward, Tabitha Ziggas

Camp Washington Edition

During a 5-week summer residency at Wave Pool Gallery in the Camp Washington neighborhood of Cincinnati in 2023, Justin Maxon completed the second volume of Field Guide to a Crisis. Justin collaborated with local artist Allonte Hart, organizer Loretta Davis, and Wave Pool’s Welcome Project Manager Olivia Nava. They worked with three halfway houses in Camp Washington and engaged members of the Welcome Project community. Each participant identified a survival tip they had learned through personal experience that helped them overcome adversity and then developed the language to teach it. Afterward, participants paired up for a “tip exchange” activity to foster the spirit of mutual aid. This process encouraged participants to share their tips and mentor each other, creating a reciprocal exchange of resources for mutual benefit.

Essay by Cal Cullen

We returned to Cincinnati by way of double rainbows, coming down from the cut in the hill with twin-colored arcs streaking across the sky. Two miles north of the river, we landed in a narrow sliver of land called Camp Washington.

“I like it here,” I stated bluntly to my driver and partner in all things, Skip.

“I think I prefer it. It’s real,” he responded. The contrast from the urine-coated sparkle of San Francisco’s tech dystopia was refreshing, to say the least. We felt at home with Cincinnati’s honest, humble, and helpful people, and this neighborhood spoke to our sense of potential and desire to create something new.

What is industry if not industrious? Camp Washington has always been a place to work hard and make things happen with what is around you. As a historically disinvested place on the city map (ironically also historically bringing in the most business taxes to the city), this center of “Porkopolis” has been left to fend for itself for several decades. Since being cut off from the city due to the construction of I-75, the neighborhood lost 40% of its housing stock, and shortly after, its neighborhood school, library, post office, and grocery store. The industry stayed; the large metalworking plants such as Reliable Castings and Meyer Tool remain large employers, along with meat packing plants, a metal recycling center, and others. But the majority of employees are no longer residents, but rather commuters who travel in.

The neighborhood is a mix of all kinds of people, which is perhaps its main draw and the main ingredient to its magic. Diversity, in all meanings of the word, finds shelter within this pocket of Italianate row houses butting up against warehouses and highway walls. My friend calls it the “armpit” of Cincinnati, and if you think of the West Side as Cincinnati’s right arm and Clifton/Center City as the heart of the city, then he’s right. The shape and geography of the map fit this description and being mostly a paved heat island nestled in a valley with the lowest tree canopy in the city, the neighborhood definitely becomes a sweaty, huddled puddle of all kinds.

The small pockets of residential housing have long-term stable homeowners mixed with new influxes of families. Along the business corridor, there are a few multi-family apartment complexes. Cincinnati is on the I-75 thoroughfare, a corridor known for human trafficking, and most of the cars spotted in the neighborhood doing quick drug deals or picking up sex workers have non-Ohio plates.

Still, the neighbor-to-neighbor connections are strong, and on any given day, you could have an unplanned philosophical discussion with people unlike you, learning things you didn’t know you needed to know and gaining unique perspectives on life, love, and survival.

Industrial spaces like the ones Camp Washington holds attract people who need space: creatives with visions to fill them with sculptures, band rehearsals, parade float constructions, sign collections and other beautiful, random, and complex offerings. The demise of Camp Washington as a traditional neighborhood with a school and a library has transitioned it into a space of potential, and the people here are busy honing their talents and interests to fill the voids.

I know a man who lives in an abandoned warehouse, not as a squatter but as a caretaker. He keeps watch for the building’s owner and builds relationships with those around him to make it work in a space with no gas, electricity, or water. He does his neighbor a favor, who is busy rehabbing another long-vacant building, by taking the demoed joists off his hands. Toting them back to the warehouse, he keeps warm through the winter by burning this found wood in a makeshift stove.

One of the artists in Camp Washington has a sponsorship deal with Duct Tape. It seems everywhere you turn, you’ll see the super sticky stuff in every color pop up, holding the neighborhood together. Another neighbor, a former metal junker until he lost his truck, has made wooden staffs for himself and his partner to traverse the urban terrain. It increases their stability and keeps them visually connected to each other.

What has always fascinated me about Camp Washington is the amount of goings-on in a place that most people consider vacant. It’s like turning over a rock in a stream and seeing a plethora of diverse life squirming and thriving underneath.

The popular neighborhood slogan “Made in Camp” was born out of this observation. Most people experience Camp Washington as a drive-through kind of place, maybe a spot to fill the tank or grab a chili dog, but other than that, not much reason to stop. The truth is, however, that the neighborhood is rich in culture and talent. What may look like a vacant warehouse from the outside holds a talented craftsman’s woodshop. What appears to be a standard row house from the sidewalk is actually a transcendent art house centered around a three-story swing. Old industrial buildings house world-class metal casting facilities, tool fabrication plants, and bustling recording studios.

It’s mildly ironic that the neighborhood now houses the nation’s largest public museum dedicated to signs via the American Sign Museum, and yet this place is still unnoticed by many. The art houses that Mark DeJong is creating (google Swing House), the innovative social practice work that Wave Pool is undertaking, the calming and centering mindfulness work at The Well, and many, many other projects that individual artists and collectives are embarking on in the area all point (in a bright neon sort of way) to the fact that this “armpit” of Cincinnati is actually a hotbed for creativity, resilience, and yes, industriousness at its finest.

A band of junk instruments made from the metal recycling center, a garden raised on ground that was formerly a gas station, a meditation garden, seaside visions of whales spurred on by sounds from the second-largest train yard in the country. Look closely, turn the rock over, and you’ll fall in love as well.

Tips

Polaroids

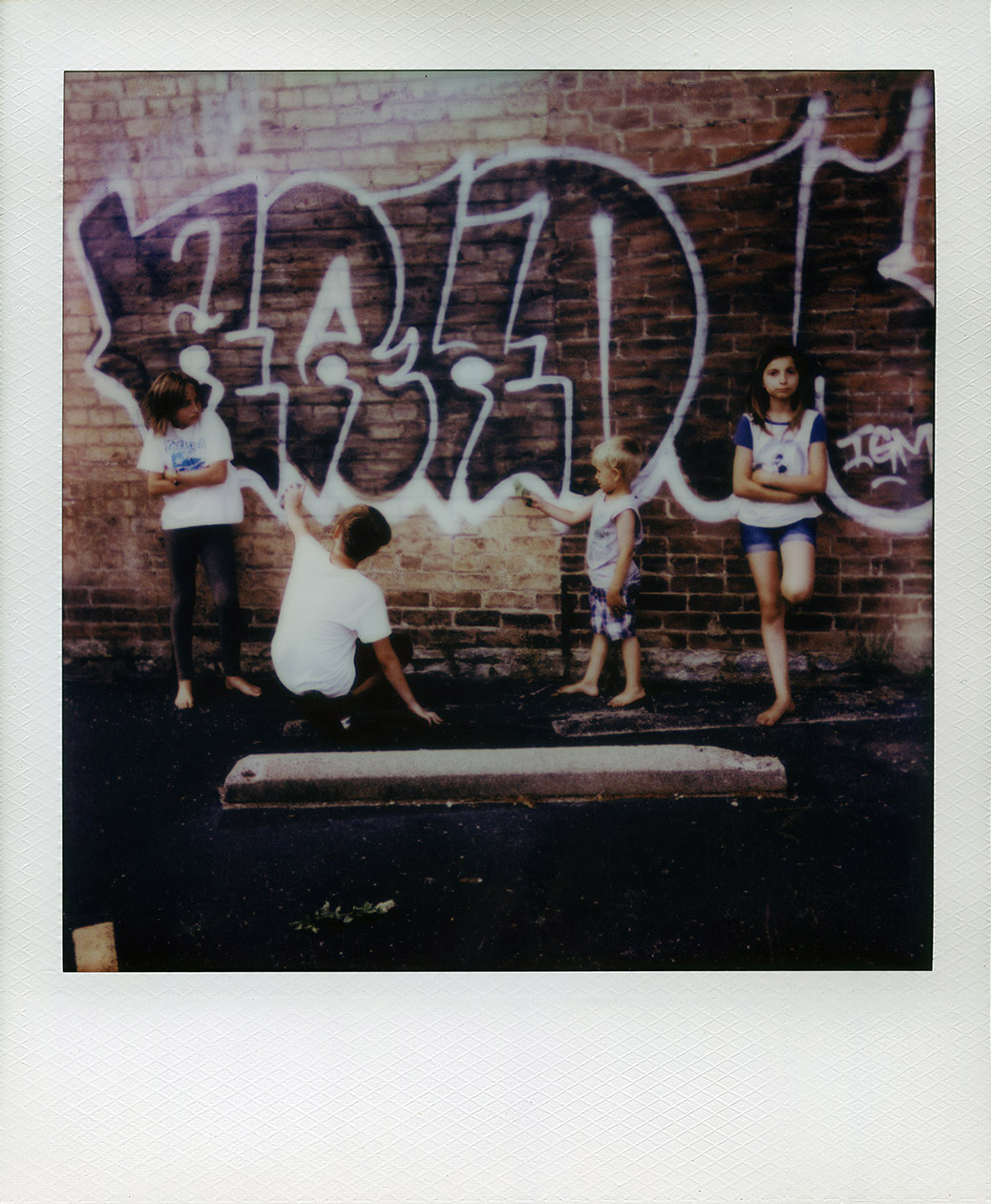

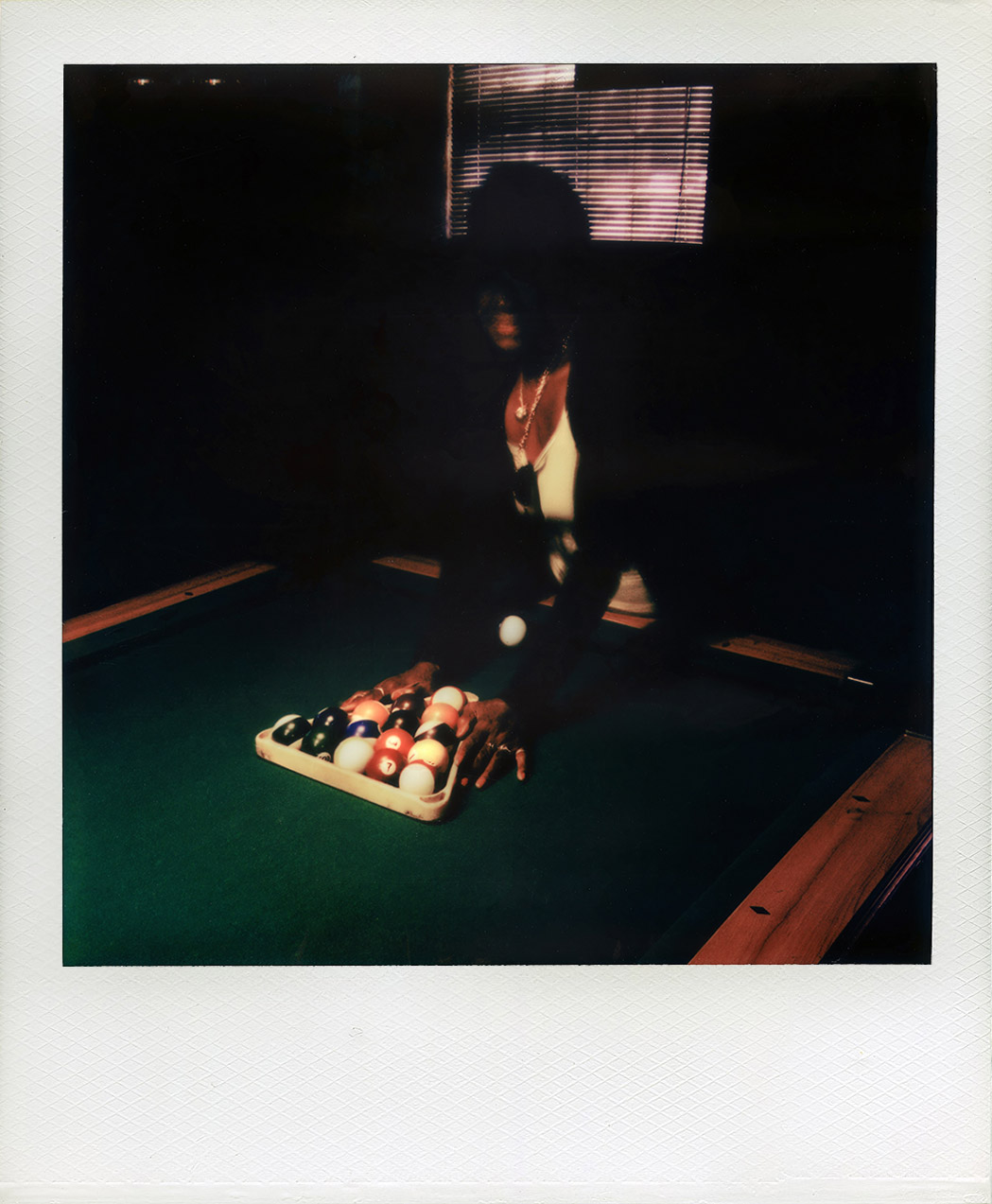

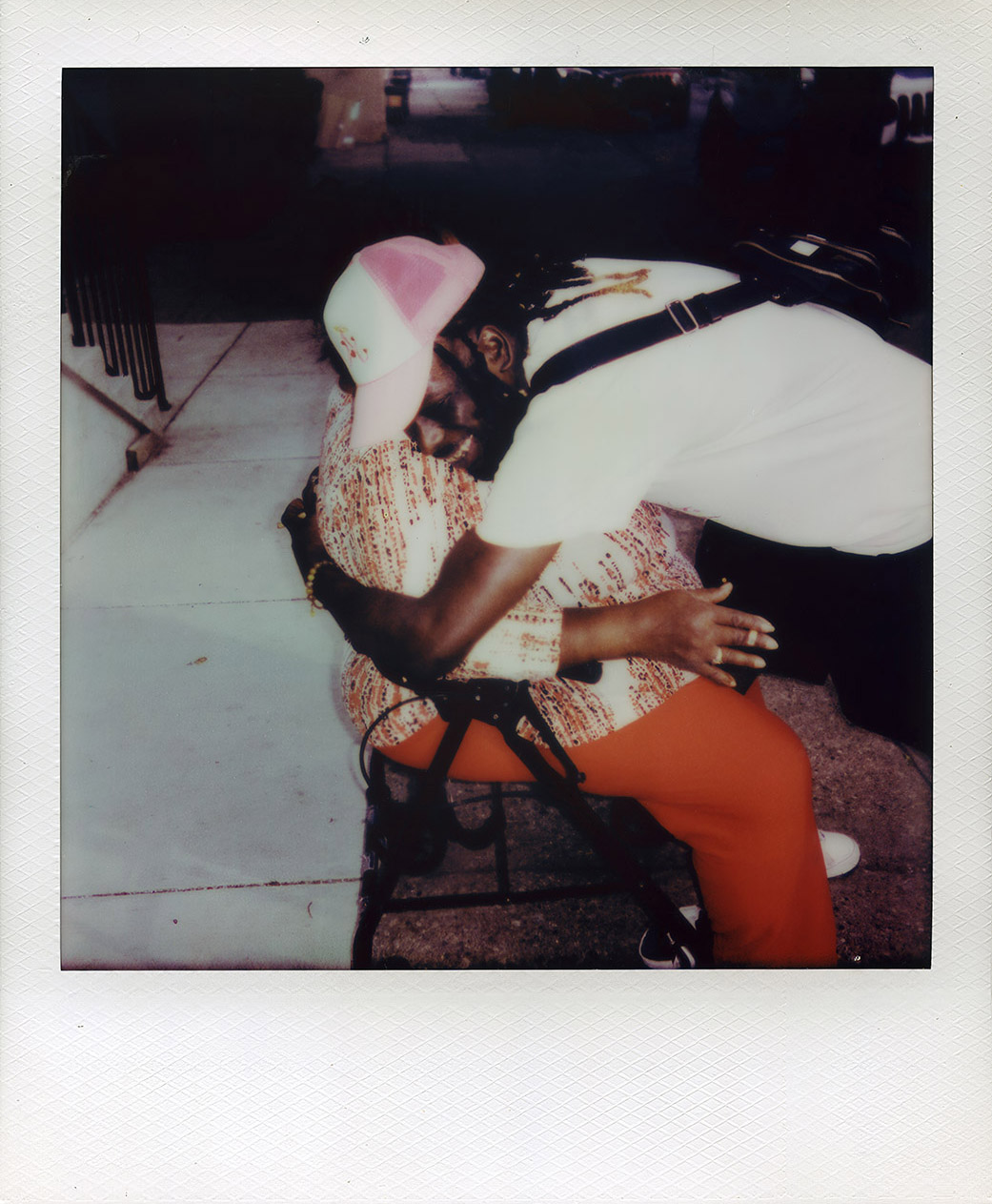

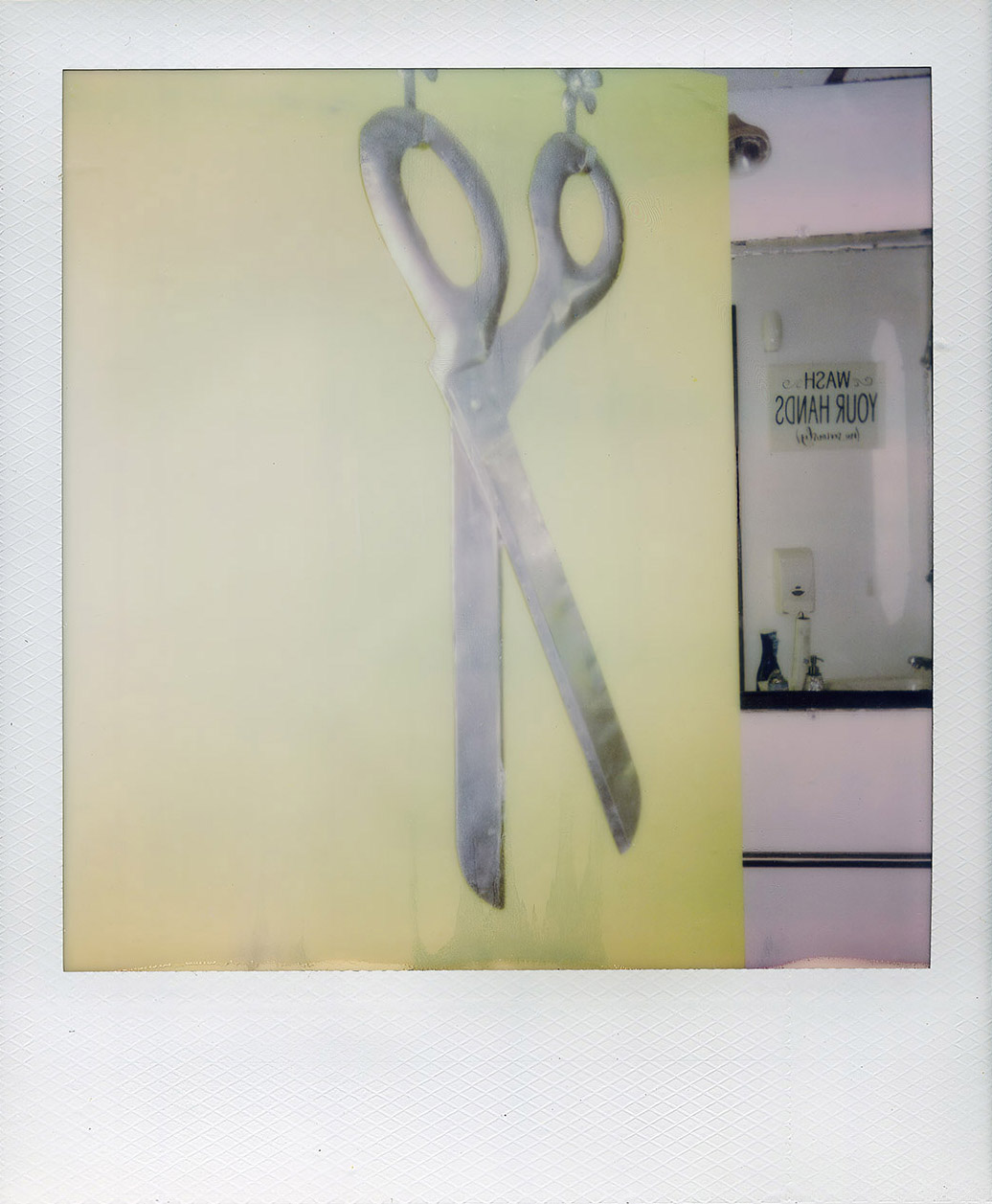

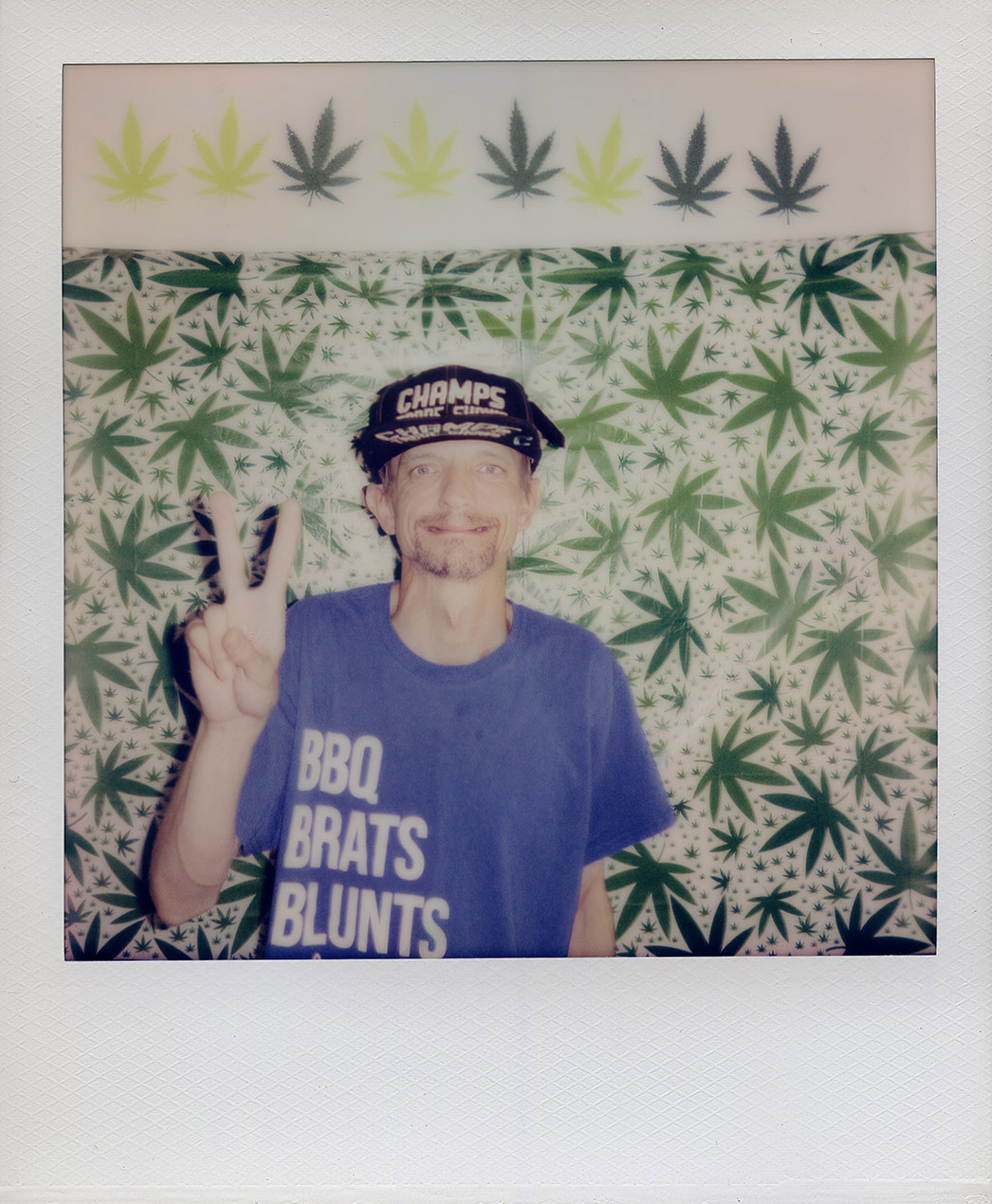

Justin and Allonte walked daily around Camp Washington, engaging people in conversation and documenting the neighborhood. The images captured the physical and social environments of the neighborhood, revealing the underlying forces that shape the lives of its residents and subtly encouraging us to look closer to uncover their hidden talents.

Book

Volume II

Limited Edition Risograph

150 copies

Published by Little Oak Press

2025

Exhibitions

Field Guide to a Crisis: The Camp Washington Edition was featured as part of the group show A Thousand Words for the FotoFocus Biennial. The opening took place on October 5, from 6-8 PM at Wave Pool Gallery in Cincinnati. The show also included the collaborative work done in Camp Washington by Rebecca Cooper and Darius Smith. It was curated by Maria Seda-Reeder. The design, curation, and installation were beautifully handled by the Public Works Collaborative, Kiersten Nash, Aubrey Murdock, and Stephen Batiz.

Talks

The project culminated at Cincinnati’s Table, a regularly occurring Welcome Project program that takes the form of a series of themed dinners to foster connections through shared meals and interactive art. Each meal centers around a theme introduced by a local artist and features food prepared by an immigrant or refugee to spark conversation and bridge divides. Focused on the theme of substance abuse, Justin, Alonte, and Sarah Northrop led a public exercise where participants shared their tips with the audience, who were then invited to contribute their own survival tips in response to a series of prompts.